Stakeholder Engagement at the Water Center

The Water Center at Penn is committed to sustainable problem-solving in collaboration with communities combatting water-related challenges in equitable and sustainable problem solving, emphasizing the necessity to apply stakeholder engagement strategies throughout this process. As I was preparing for my fieldwork, I was curious about the Water Center’s guiding principles for stakeholder engagement– ensuring that communities directly impacted by these issues have a primary seat at the table in addressing them. How can we approach stakeholder engagement and creative problem-solving in the context of numerous and varying perspectives? How do we balance these voices when addressing the environmental needs of an urban neighborhood? What are the appropriate means of introducing climate resilience methods to a community?

In a comparative study of the local community and urban communities in the Netherlands, I had the opportunity to address this topic through my involvement in both the Water Center and Penn Abroad’s partnership with the Eastwick community in Philadelphia. Built atop what used to be the 1900 Tinicum Marsh in the Delaware Bay Tidal Zone, the Eastwick neighborhood is at high risk of flooding overflows from the Cobbs Creek and Schuylkill River, as well as storm surges from the Delaware River. The community faces additional environmental hazards due to its proximity to the superfund site where the unregulated Clearview Landfill was active from the 1950s to the 1970s. The Water Center –along with other stakeholders such as the City of Philadelphia, the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority, Temple University, NOAA, the EPA, Eastwick Friends and Neighbors, Drexel University, the US Army Corps of Engineers, Penn Perelman School of Medicine, and many other partners– works in collaboration with Eastwick United, Eastwick’s representative community board, to address the multifaceted impacts felt by the community. Throughout my fieldwork with the Water Center and my participation in Dr. Simon Richter’s Penn Global Seminar, I helped plan the presentation logistics for this comparative study; proposed informed suggestions for the community; designed the marketing material for the event; and traveled to the Netherlands and to Eastwick in order to execute the study. (Center for Participatory Research, n.d.; Eastwick Presentation, n.d.)

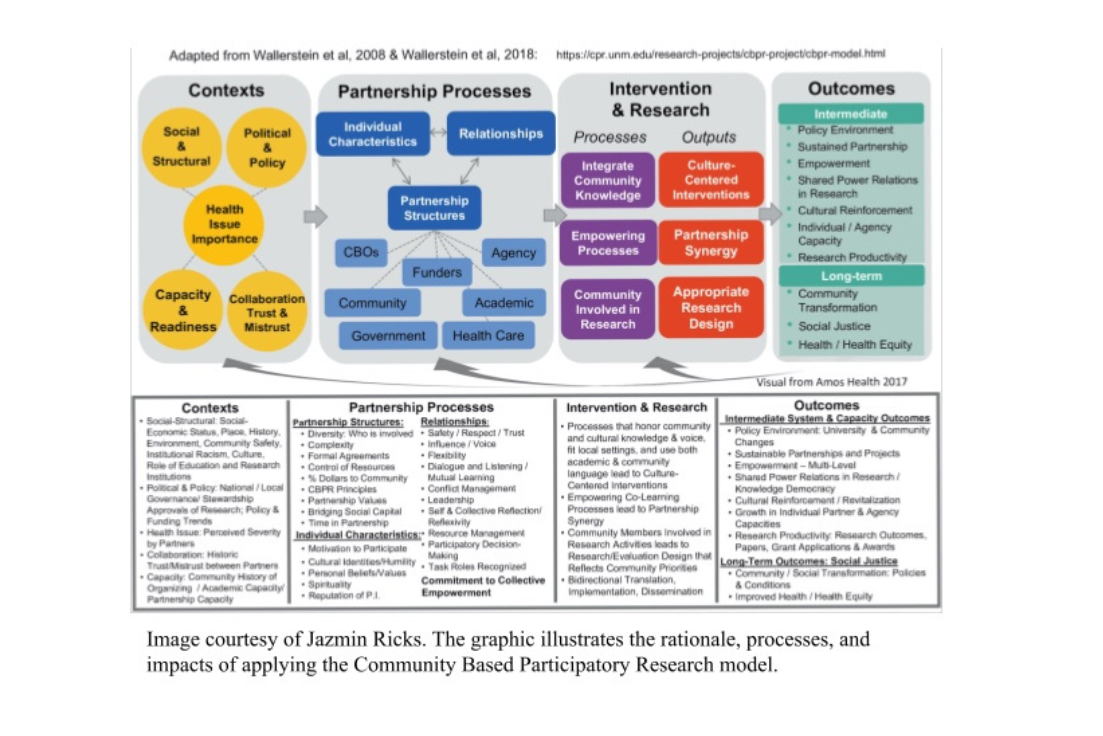

In a Q&A session attended by Eastwick United, the City of Philadelphia, the Water Center, and Drexel University representatives, a community member from Eastwick United spoke of the necessity for empathy in stakeholder engagement activities and pushed for a “steering committee” to enforce “equitable decision-making” as opposed to just “equitable problem-solving.” Althoughstakeholder engagement methodology is largely absent within the environmental science field, the Water Center considers a public health perspective in its collaborations, making efforts to apply the principles of Community Based Participatory Research (CBPR) in its operations (Jazmin Ricks, personal communication, May 4, 2023). CBPR is defined as “a collaborative research approach that is designed to ensure and establish structures for participation by communities affected by the issue being studied, representatives of organizations, and researchers in all aspects of the research process, to improve health and well-being through taking action, including social change” (Ricks, n.d.). It integrates the involvement of community members in all aspects of research, from reaching out to partners to constructing research and intervention methods. In doing so, the model encourages long-term equitable relationships and community improvements. (Ricks, n.d.)

Upon inquiring about the CBPR model with my mentor Jazmin Ricks, she made the concept concrete by explaining the potential role that a community advisory board may play in constructing a concise community narrative on environmental justice issues. By including this advisory board on grant proposals, the creation of a community advisory board creates a mechanism through which the community may make funding decisions and, thus, demonstrate some form of economic independence and autonomy over the larger decision making processes resulting from research (Jazmin Ricks, personal communication, May 4, 2023). The values of the CBPR model are also demonstrated in the Water Center meetings for planning the trip and final presentation. Amongst the logistical aspects of planning were constant reminders of a differentiation between imposing suggestions onto a community as external researchers and providing observations of a local case study.

Despite the recognition of a clear vision for effective stakeholder engagement in Eastwick and the attempt to apply various methodologies for this purpose, all panelists at the aforementioned Q&A session also acknowledged the difficulty synchronizing agendas in the orchestration of a “win-win-win” scenario. This is the result of the varied and numerous partners working with this community in different capacities. These relationships are further complicated by elements of distrust between residents, the private sector and the City of Philadelphia. The residents have historically been subject to racially-motivated environmental injustice and gentrification.

My travels to the Netherlands for this project enabled me to consider stakeholder engagement methods through the lens of public policy and urban studies. During our roundtable discussion with Resilient Delta at TU Delft and Erasmus University of Rotterdam, Dr. Theresa Audrey Esteban introduced her Collective Engagement Urban Resilience Framework (CEURF), which objectively addresses the interaction between different government and non-government stakeholders in the effort to achieve climate resilience within an urban space. Esteban asserts the city’s “adaptive cycles”– measured through collective concern, collective action, collective efficacy, and collective security– as they are propelled by its social, institutional, human, environmental, and economic capitals. The CEURF provides a multidisciplinary lens through which climate resilience may be defined and evaluated within a specific city. (Esteban, 2021)

My travels to the Netherlands for this project enabled me to consider stakeholder engagement methods through the lens of public policy and urban studies. During our roundtable discussion with Resilient Delta at TU Delft and Erasmus University of Rotterdam, Dr. Theresa Audrey Esteban introduced her Collective Engagement Urban Resilience Framework (CEURF), which objectively addresses the interaction between different government and non-government stakeholders in the effort to achieve climate resilience within an urban space. Esteban asserts the city’s “adaptive cycles”– measured through collective concern, collective action, collective efficacy, and collective security– as they are propelled by its social, institutional, human, environmental, and economic capitals. The CEURF provides a multidisciplinary lens through which climate resilience may be defined and evaluated within a specific city. (Esteban, 2021)

Ultimately, Eastwick’s ability to enact resilience solutions is greatly limited by its capital. Eastwick United consists of only two volunteers and a community board on a volunteer basis, which makes coordinating their different partnerships increasingly difficult. Moreover, there are no readily accessible economic resources at Eastwick United’s disposal. While Eastwick is written on many grants, Eastwick United itself is never holding and managing the money for itself and, thus, lacks funding power and the fundamental ability to say no. While the community has many partners helping to address their environmental risk, fragmentation and power dynamics may still be derived not only from monetary resources but also in access to learning tools and the like. Until there is a shift in the balance of power, achieving reciprocal collaboration at the decision-making level will be extremely difficult to achieve. (Jazmin Ricks, personal communication, May 4, 2023)

“A private stakeholder. That’s what might encourage alignment between the government and the community in investing in managed retreat.” This was the instinctive answer that my classmates and I discussed as we were rushed from meeting to meeting. While addressing a missing aspect of funding and affordability in Eastwick’s proposal to relocate amongst immense flood risk, our solution was ultimately more complicated than our initial assessment. It would’ve been ineffective in the sense that this solution did not take into account the trauma surrounding the presence of private corporations after the development and sale of land environmentally unfit for living according to human health standards. The hasty inclusion of private sector stakeholders ignores the fear of gentrification and loss of community throughout Eastwick. This important perspective on community history and culture was provided by an Eastwick resident that joined our study in the Netherlands. To me, her intervention illustrates the necessity for effective community engagement in yielding effective problem solving. As I continue to learn about stakeholder engagement, I am excited to better understand the concept at the international level as international collaboration becomes increasingly crucial to building resilience amidst the growing climate crisis. In particular, I am curious to learn more about the dynamics of developed and developing nations in this pursuit throughout my senior thesis on climate resilience in the Philippines.

Works Cited

Center for Participatory Research. (n.d.). Retrieved May 6, 2023, from https://hsc.unm.edu/population-health/research/center-participatory-research/

Eastwick Presentation. (n.d.). Retrieved May 5, 2023, from https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/12oyOvumNjQnLu4zlOh4ieyX4IUQkgG8shTd5WNueApU

Esteban, T. (2021). Collective engagement: From disaster-prone to disaster-resilient city [Doctoral Thesis].

Jazmin Ricks. (2023, May 4). [Personal communication].

Ricks, J. (n.d.). CBPR Resources Presentation. Retrieved May 6, 2023, from https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1VE-uB_rwISuiyuwZO42EOk3S4IzPfOSiwRu-Go2E-fA

- Community Capacity Building & Water Equity

- Water Leadership