Sustainability Assessment of AMAL Arsenic Removal Units in West Bengal, India

The Bengal basin, encompassing large tracts of Bangladesh and the Indian state of West Bengal, is home to more than 2% of the world’s population. The basin’s sediments contain high levels of geogenic arsenic which pollutes groundwater resources at concentrations exceeding safe drinking standards of both the Bureau of Indian Standards and the World Health Organization. In West Bengal alone, it is estimated that over 50 million people remain exposed to unsafe water even after decades of interventions by the Indian Government and external NGO actors to either remove arsenic from groundwater resources or supply communities with alternatives. Toxic levels of arsenic consumption result in a variety of health impacts including skin, bladder, and lung cancers, neurodegenerative disease, impaired lung function, hypertension, birth complications, and skin lesions.

The AMAL Arsenic Removal Unit (ARU) was developed in collaboration between the Indian Institute of Engineering and Technology and Lehigh University in the late 1990s. With funds from the Hilton Foundation, Rotary International and later, Water for People, the ARU was implemented in roughly 150 communities to deliver potable water to an estimated population of 150,000. As funding agencies usually only provided financial support and technical oversight for the installation of the system and ARUs require regular upkeep, the long-term sustainability of the program is a challenge.

In January 2020, a small team of Penn student researchers traveled to West Bengal to conduct an independent sustainability assessment of the AMAL ARUs. Through qualitative observations and interviews with community members, NGO representatives, and local entrepreneurs servicing the devices, 15 AMAL ARU programs were evaluated. Preliminary findings were presented at the 13th Annual Global Water Alliance conference in Kolkata. Findings, as well as program success factors and recommendations, are presented below.

Findings

Our assessment developed a scoring criterion-based off 20 indicators of success isolated from interviews with community members of the highest performing programs. Though the small sample size (15) precluded rigorous statistical analysis, we found significant discrepancies between programs unable to provision drinking water below the as-designed arsenic limit (or, show the water was safe with testing documentation) and those serving their communities as intended. These discrepancies informed our program recommendations.

We found that water committees associated with local clubs (sporting, philanthropic, etc.) scored higher than independent programs. The AMAL arsenic removal units also scored higher when developed in urban or peri-urban contexts, in comparison to rural communities. We also found that 90% of water quality tests we received from water committees passed the as-designed limit of 0.05mg/L total arsenic concentration. However, the Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS) recently reduced the permissible limit to 0.01 mg/L, which challenges the performance of the AMAL units.

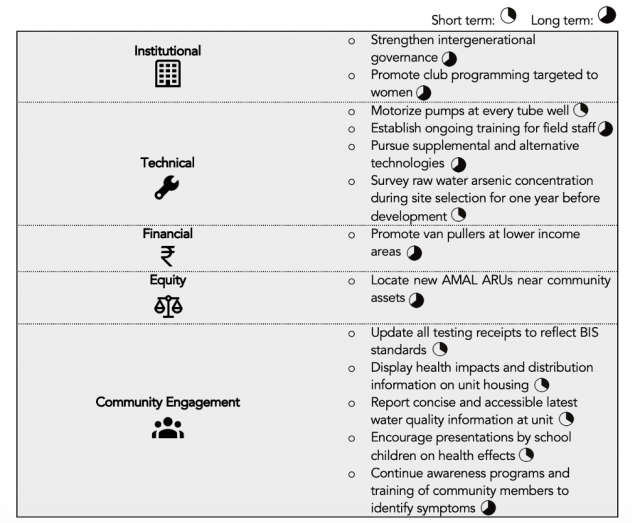

For recommendations, we highlighted the importance of motorizing the pumps at all tube wells where the AMAL units are installed, as the ease-of-use benefits proved to ensure usership (at one site, the number of paying families increased over 800% after a motor was installed). We recommended that awareness information on the health impacts of arsenic consumption are displayed at the unit’s housing – this practice was found in many of the highest performing programs. We also recommended that local NGOs promote women’s programming in clubs associated with water committees, as we found the lowest levels of women’s participation in water governance when committees were associated with clubs focused on men’s programming. For a long-term or aspiration recommendation, we included the training of local maintenance entrepreneurs on supplemental or alternative technologies to improve older units to current BIS and World Health Organization standards. A full list of our recommendations is included below.